Deviant Viewers and Gendered Looks:

Erotic Interactions with Images and Visual Culture in Song Religion

Hsiao-wen Cheng

Hong Mai’s (1123-1202) Yijian zhi (Record of the Listener) records a story about the encounter between a prostitute and a horseman statue in the Temple of the Miraculous Manifestation Prince in Yongkang Garrison (Sichuan):

Outside the temple gate, she saw [the statue of] a grand, tall horseman who had a magnificent appearance and physique. The embroidered fabric on both of his thighs seemed to be fluttering. She fixed her eyes on him and was so enamored that she could not leave until dusk, when people from her household forced her home. She felt dejected, as if she had lost something. The next day, a guest who resembled the horseman asked to stay the night. The prostitute was overwhelmed with joy and thought it must have been a belated yet destined encounter. The man left at dawn and returned at dusk. After staying for several nights, he suddenly wept and said to her, “In fact, I am not human but a horseman in the temple. Because of your affection, I broke the rules and came to you. I repeatedly skipped my nightly duties and was caught by my superior. I was found guilty and tomorrow I will be beaten on the back with a stick and exiled to perform penal labor. Please buy more paper money [as mortuary or sacrificial offerings] for the time when I pass your door.” The prostitute also wept and promised to do as asked. When the time came, the man carried an iron cangue, blood dripping all over his body, and his face was tattooed [with the characters] “dispatched to such-and-such place.” Two robust soldiers escorted him. He passed by the prostitute’s house and bade farewell. She set up a table of sacrifice, burned paper money, and, weeping, saw him off. When she visited the temple again, the statue had already toppled to the ground.

What do we make of such a story?

A key question that I had in mind when writing this paper is: What did icons in popular temples do in Song people’s eyes? We know that those images were not simply visual representations. Deities inhabited in them. But it seems to me that icons were not just the lodgings of deities, either. Religious icons created the very existence of divinities and spirits. Song people expected the images that they made (or commissioned) for their temples to become real divinities—or demons if they crossed the line. To create a cult involved creating a pantheon for the god by staffing its temple with divinities in various capacities.

Some Song statues were made in life size, such as the Hārītī (161 centimeter tall) in Shimenshan niche no. 9, in Dazu, Sichuan (Southern Song):

Guo Xiangying and Li Shumin eds., Dazu shike diaosu 大足石刻雕塑全集 (Chongqing: Chongqing chubanshe, 2000), vol. 4, plate 66.

Another question that interests me is about the new narratives of women’s desire in the Southern Song and the Yuan. In some stories, there was an intriguing combination of women as active beholders and a complete absence of any description of those women’s appearances. The story of the prostitute and the horseman statue is an example. Narratives of women as active agents of desire in response to religious images emerged almost concurrently with the new medical attention to female sexual desire. Elite medical writers incorporated folktale narratives into their medical case histories.

Bird’s the Word: Birds and Pure Land Practice

Kendall Marchman

A recent popular Reddit post featured a video of a goose walking in formation with Buddhist nuns as they perform nianfo, recitation of the name of Amitābha. In another video released by Dharma Drum Mountain, a nun explains how a baby bird she rescued began to recite the name of Amitābha.

While at first glance these cases might just seem like humorous demonstrations of playful Buddhists, there is actually a significant history of birds and Pure Land practice. This connection begins with the Buddha’s description of Amitābha’s Pure Land in the Smaller Sukhāvātīvyūha Sūtra:

Again, Śāriputra, in that land there are always many kids of rare and beautiful birds of various colors, such as white geese, peacocks, parrots, śaris, kalaviṅkas, jīvaṃjīvakas. Six times during the day and night birds sing with melodious and delicate sounds, which proclaim such teachings as the five roots of good, the five powers, the seven practices leading to enlightenment, and the Noble Eightfold Path. On hearing them, all the people of that land become mindful of the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. Śāriputra, you should not assume that these birds are born as retribution for evil karma. The reason is that none of the three evil realms exists in that Buddha land. Śāriputra, even the names of the three evil realms do not exist there; how much less the realms themselves! These birds are manifested by Amitāyus so that their singing can proclaim and spread the Dharma. (T.366 347a16-24; translation from The Three Pure Land Sutras, trans. Hisao Inagaki and Harold Stewart, (Moraga, CA: BDK America, Inc., 2003), 92)

The birds are the only non-human residents of the Pure Land, and since the popularization of Pure Land practice in medieval China, they have continually captured the attention of Pure Land practitioners.

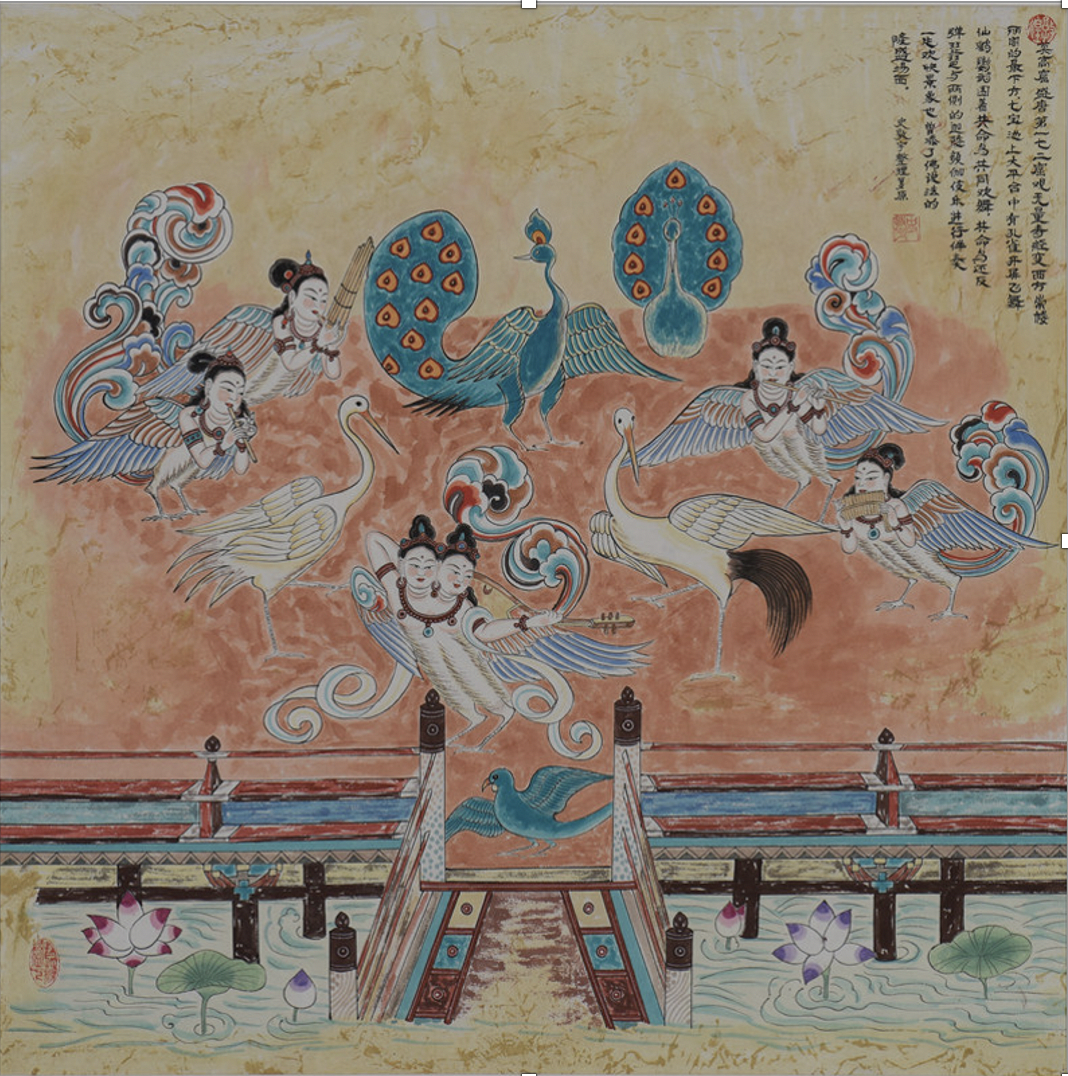

Kalavinka in the Amitayurdhyana Sutra Cave 172, Mogao Caves. Tang Dynasty (650-820). Recreated by SHI Dunyu 史敦宇. Collected by NCPA.

The birds frequently appeared in illustrations of the Pure Land, like this portion of a recreated mural in a Dunhuang cave. Early advocates for Pure Land practice in China, including Daochuo, Shandao, Huaigan, and others also highlighted the Pure Land birds to demonstrate that it was superior to all other options for rebirth. And, like today, accounts began to pop up that suggested that the birds are not exclusive to the Pure Land, but occasionally appear here on earth!

In my article, I take a closer look at how scriptures, commentarial literature, liturgical texts, and popular accounts all feature the birds of the Pure Land. I suggest that there’s more to their popularity than the ornamental beauty they add to the Pure Land. They help Buddhists imagine the Pure Land as they await and hope for their rebirth there, but also allow them to experience a glimpse of the Pure Land through interactions with birds and their songs. In other words, the birds aren’t just skillful tools in the Pure Land, they allow reflection and experience of the Pure Land in each present moment.

The Confluence of Karma and Hygiene:

Vegetarianism with Renewed Meanings for Modern Chinese Buddhism

Lianghao Lu

From the 1920s onward, Master Taixu, the prominent monastic leader known for his reformist stand, came to be an endorser of a product, 和合粉, a gourmet powder. His advertisement of the product appeared in both secular press, such as Shanghai News 申报, and in Buddhist periodicals like The Sound of Sea Tide 海潮音. This interesting linkage between a Buddhist monastic, the press, and a seasoning product advertised to vegetarians denotes the intricacy of vegetarianism as a discourse standing at the crossroads of the Chinese tradition and a modernizing society. Vegetarianism, a practice closely associated with but not solely monopolized by Buddhism, is a prism reflecting the entangling issues of the emerging scientific rationale, the preservation of the Buddhist practice, and the fusion of a Chinese tradition with Western progressive ethos. My article hence explores discussions that took place in the Buddhist periodicals regarding vegetarian practice, and illustrates how the confluence of scientific rationale and the continued Buddhist karmic argument ultimately renews the discourse of vegetarianism in modern China.

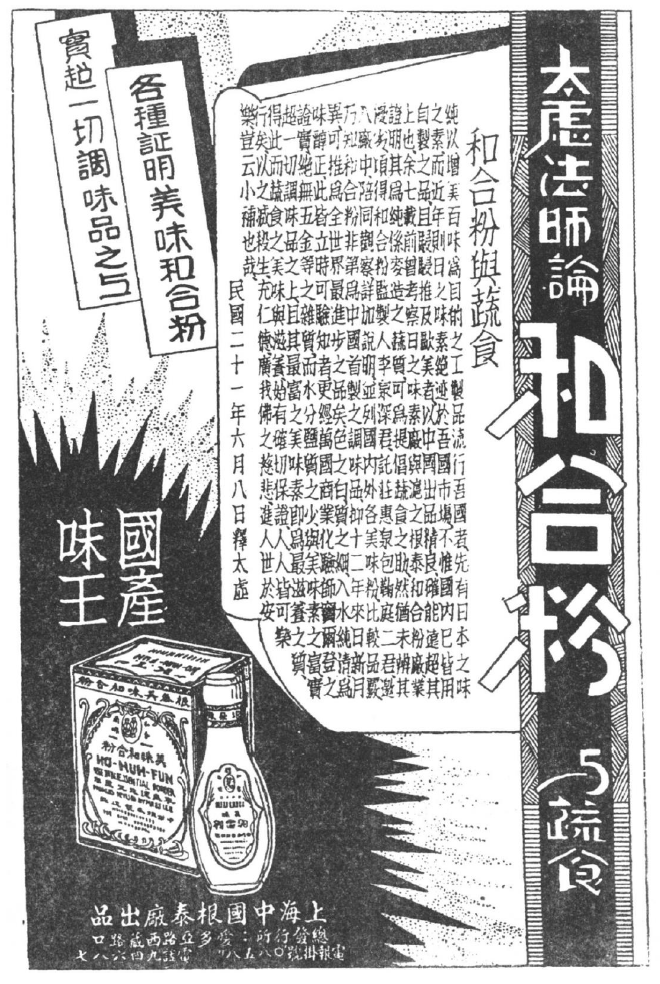

Taixu’s advertisement for 和合粉 captures some of the key themes in the renewal of Buddhist vegetarianism discourse in modern China: (1) the emphasis on the benefit of vegetarianism from a Buddhist morality perspective while criticizing the consumption of meat, (2) the illustration of the scientific and industrial manufacturing processes, (3) and employing the term “evolution” to justify the superiority of the product. These themes frequently appeared in the promotional texts for vegetarianism in the Buddhist periodicals closely associated with Taixu.

An advertisement of 和合粉 in The Sound of Sea Tide, 1932-09-15.

An advertisement of 和合粉 in Shanghai News, 1925-08-16.

However, besides embracing the vogue trend of scientific reasoning, the Buddhist masses were more concerned about their day-to-day religious practice. Therefore, represented by Yinguang and Dixian, another cluster of Buddhist authors in the periodicals resorted to the karmic argument and personal experience to justify the practice. The emphasis on the daily practice came with innovation as well, exemplified by the promotional campaign for a vegetarian soap. Yinguang was one of the main initiators, and his disciples, such as Desen 德森, made great efforts to continue the campaign after Yinguang passed away in 1941. This vegetarian soap movement infused the karmic discourse of vegetarianism with a uniquely modern consciousness.

An Advertisement of Vegetarian Soap on Awakening News Monthly 覺訊月刊, 1949-08-01.

The article finds convergence in the case of Lü Bicheng, who interacted with both Taixu, Yinguang, and Dixian. Lü’s writing frequently appeared in the Buddhist periodicals, through which she introduced the Western vegetarianism and animal protection movements, thus enabling Chinese Buddhists to perceive their vegetarian practice in light of the international progressive ethos. Lü underpinned the rationale of vegetarianism through Buddhist apologetics and evaluated the Western counterpart movement through such lens, coinciding with the vision of the reformist Buddhists, who posited Buddhism as the ultimate solution to their perceived world civilization crisis.

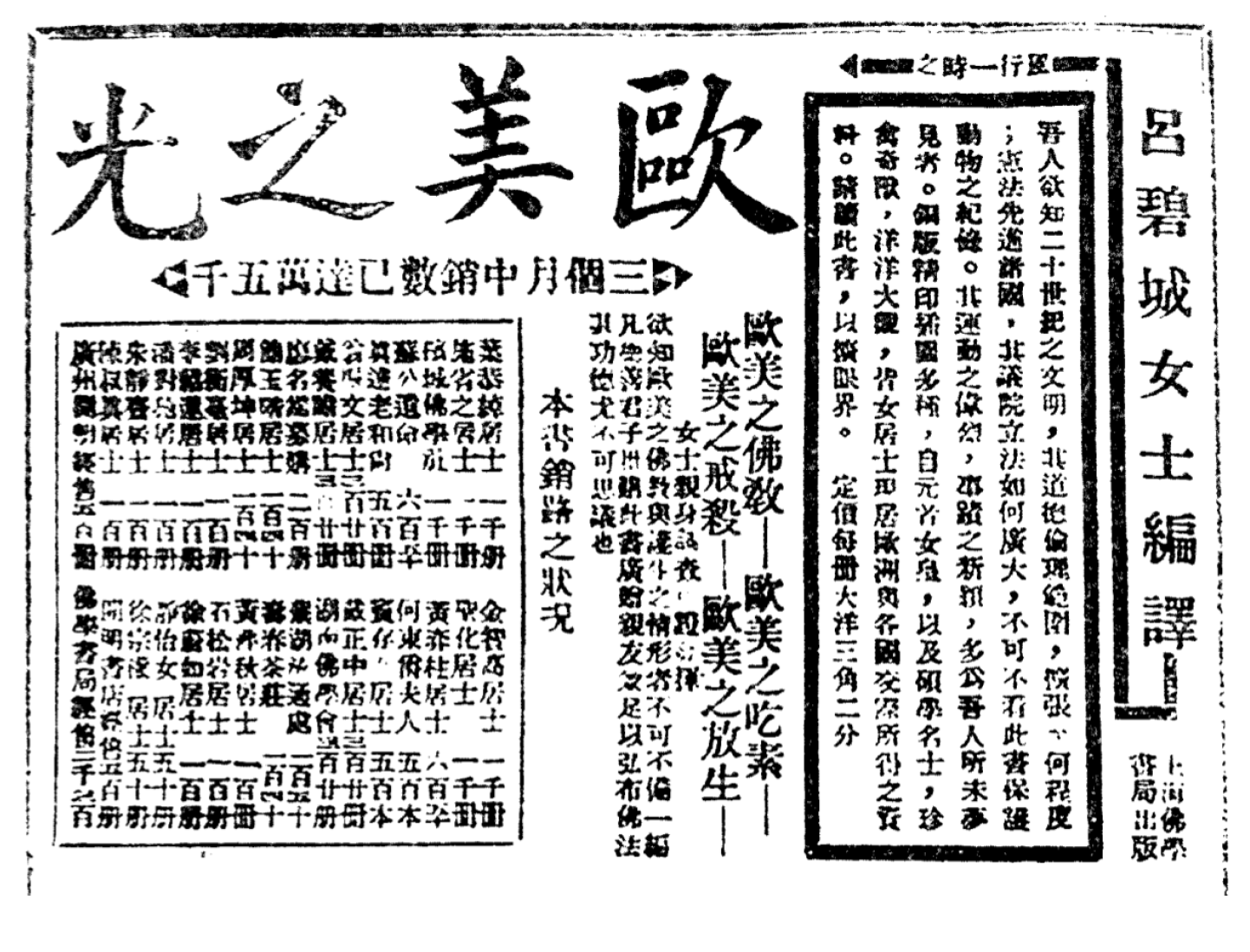

An advertisement for Lü’s book The Light of Europe and the Americas 歐美之光 in Buddhist Semi-monthly 佛學半月刊, 1932-01-16.

Essentially, this article argues that various authors, through the Buddhist periodicals, jointly contributed to form a large repertoire of updated interpretations and legitimatizing rhetoric for Buddhist vegetarianism with hybrid characteristics of both modern Western knowledge and traditional meanings, hence resulting in a modern Chinese Buddhist discourse of vegetarianism with lasting influence till this day.