Vernacular Modernism: Humanistic Buddhism from Below in Bade, Taiwan

Justin R. Ritzinger

On a hot summer night in late June 2018 in a small Buddha Hall ensconced above a failed vegetarian restaurant in a poor neighborhood of the Bade 八德 district of Taoyuan 桃園, Taiwan, a man and woman sit face-to-face earnestly discussing a text. The Buddha Hall is known as the Maitreya Lay Buddhist Lodge (Cishi jushilin 慈氏居士林). The man is Brother Zhong 鐘師兄, a former gangster in his 60s and the Lodge’s founder and resident teacher. The woman is Sister Juejia 覺佳師姐, the thirty-four-year-old director of the youth program and a recovering amphetamine addict who repairs shoes in the market with her father. She first became involved with the Lodge when Brother Zhong helped her to escape an abusive boyfriend by unlocking the power of the Dharma through repentance and merit-making. The text they are poring over is a commentary by the great twentieth-century scholar-monk Yinshun 印順 on Nagarjuna’s profound and difficult Treatise on the Middle (zhonglun 中論). They have been working through the treatise every Monday and Wednesday evening for the last several weeks so that Juejia can gain the insight into emptiness that will allow her to treat all the children in the youth program equally. Such youth outreach is central to the Lodge’s mission to help revitalize Buddhism and establish the pure land on earth (renjian jingtu 人間淨土).

Figure 1: Exterior of the Maitreya Lodge in 2016.

Figure 2: Preaching dais.

Figure 3: Main shrine with the Tuṣita trinity above and the Saha trinity below.

This is not the type of place or the sort of people that has typically occupied the attention of scholars of Buddhism in Taiwan. Instead, our gaze has been largely focused on the large, sophisticated multinational organizations known in Taiwan as the “great mountaintops” (da shantou 大山頭): Foguang shan 佛光山, Tzu Chi (Ciji 慈濟), and Dharma Drum Mountain (Fagu shan 法鼓山). These groups are presented as the fulfillment of the Republican-era reforms of Taixu 太虛 and a product of the social dynamism unleased by Taiwan’s economic miracle and democratization. Yet these organizations, while impressive and influential, are a smaller and less representative segment of the Buddhist landscape than one might assume.

This article allows us to glimpse some of what we have been missing by considering Buddhism in Taiwan from a different angle: not from above, but from below; not through multinational monastic-led organizations, but through a neighborhood lay community; not as a discrete tradition, but as part of a broader religious field. At the Lodge, we find a “vernacular modernism” in which core ideas and orientations of Buddhist modernism are articulated within a broader religious field marked by enduring dynamics and tensions identified in studies of late imperial Chinese religion. While the Lodge illustrates this phenomenon in a particularly vivid way, it is unlikely to be unique and there is reason to hope that the concept with prove useful to other inquiries.

Revisiting the Xiaoshi Jingang keyi 銷釋金剛科儀:

A Textual and Reception History

Kedao Tong

Attributed to a Chan monk active in the final decades of the Southern Song dynasty, the Xiaoshi Jingang keyi (Liturgical Manual that Explicates the Diamond Sūtra) is a reasonably familiar text among scholars of Chinese popular religions, Ming-Qing literature, and Chinese Buddhism. A text named Jingang keyi is performed by two preachers from a nunnery and quoted at length in the Plum in the Golden Vase, the well-known late Ming vernacular novel. In one of the works in the Five Books in Six Volumes, a sectarian scripture dated to the early sixteenth century, the nighttime recitation of the Jingang keyi by a group of Buddhist monks in a funerary setting reportedly inspires the soon-to-be Patriarch Luo to attain awakening. With its focus on a popular Buddhist scripture and its incorporation of ritual processes, the Xiaoshi Jingang keyi has received attention for the light it sheds on Buddhist scriptural cultures.

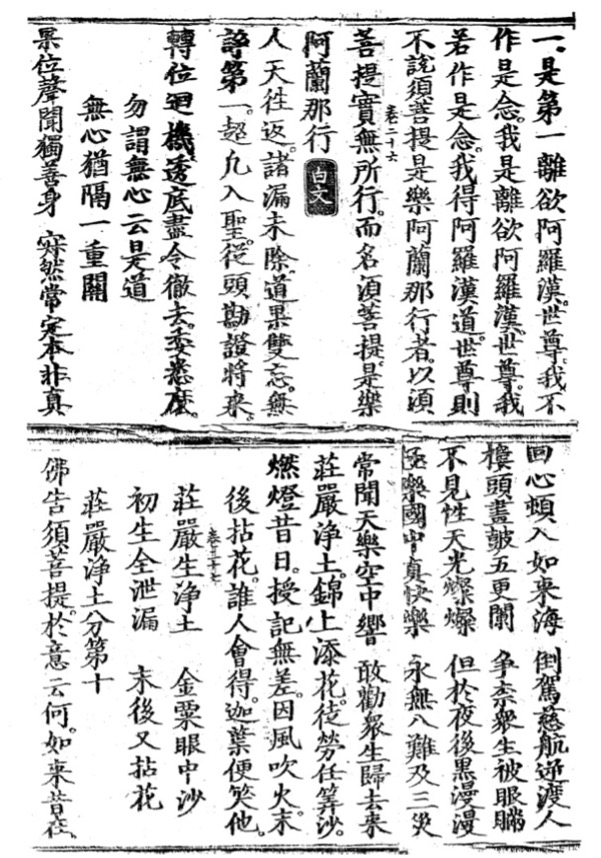

Portions of Section 9 of the Xiaoshi Jingang keyi 銷釋金剛科儀. 1528. Woodblock print. Reproduced in Ming Qing minjian zongjiao jingjuan wenxian 明清民間宗教經卷文獻, 1: 25.

The current article reconsiders the Xiaoshi Jingang keyi by situating it in the mainstream Chinese Buddhist scholastic and ritual literature associated with the Diamond Sūtra before roughly the thirteenth century, and by looking at the commentaries on it by Buddhist monastics in the Ming era. For this purpose, this article uses the earliest extant, full-length, and free-standing edition of the Xiaoshi Jingang keyi, dated to 1528, and cautions against mixing it up with other recensions and similarly titled texts that survive in manuscript and printed forms.

Through analyses of the various components of this multi-part text and readings of the content, this study illustrates its connections with the pre-existing Chinese Buddhist literature on the Diamond Sūtra with respect to the structure, source material, and the use of verses. My examination of the existing commentaries and annotations on the Xiaoshi Jingang keyi shows that it had audiences in various regions of Ming China before the mid-sixteenth century and in Goryeo and early Joseon Korea. While much of the fame of the text in modern scholarship derives from its associations with popular religions and the baojuan or precious scrolls literature, this article suggests that it is equally important to give attention to the milieu in which the Xiaoshi Jingang keyi was originally produced and its reception in monastic Buddhist circles for a fuller understanding of its place in the history of Chinese religions.