The Concept of the Soul During the Chinese Rites Controversy:

The Example of Xia Dachang

Wang Xueying

Soon after Matteo Ricci started his missionary work in China, he realized that there was no Chinese term equivalent to the Christian concept of the anima—a human soul that is individual, spiritual, and immortal. To develop this concept in Chinese, Ricci creatively invoked Chinese ancestral sacrifices, arguing that the sacrifices are made to the individual, immortal souls (linghun 靈魂) of deceased ancestors. Ricci’s strategy, after enjoying decades of success, was called into question during the Chinese Rites Controversy, when mendicant missionaries condemned ancestral rites as idolatrous. Chinese converts, who hoped to continue practicing ancestral rites, argued that the rites were merely an expression of gratitude, which does not involve the “reception” of sacrifices by the ancestors. But the question is, how should they then explain the concept of the anima to fellow Chinese?

In this article, I examine the conception of the soul by Xia Dachang 夏大常 (before 1624–after 1686), a Confucian literatus who converted to Christianity at the turn of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A close reading of Xia’s treatise On the Soul suggests that he uses the framework of Mencius’s xing shan 性善—that human beings are by nature good—to explain the concept of the soul. Xia’s conception of the soul represents one way in which the concept of the soul could be received by Christians who were deeply influenced by Confucianism.

In the Shadow of the Spirit Image:

The Production, Consecration, and Enshrinement of a Daoist Statue in Northern Taiwan

Aaron K. Reich

In the course of creating a spirit image (shenxiang 神像), statue carver Chen Kuanhong 陳寬宏 (b. 1977) explains, “the energy (lit. the essence [jing 精], breath [qi 氣], and spirit [shen 神]) of its maker becomes absorbed into the work the art” (製作著的精氣神貫注於作品中). Accordingly, as he carves a statue, he aims toward shaping an outer appearance so refined it appears “as if a spirit enters [the statue] and emits its light” (如有神入發其光). In the act of artistic creation, the divine light or radiance (guang 光) of the god transmits through the artist’s body into the statue, and from within the material this light shines forth into the world. The statue thus emerges as an extension of its maker, born in the balance between inherited technique and creative improvisation, a continuation of the artist’s energy, breath, and spirit (see fig. 1).

Figure 1: Professional Carver Chen Kuanhong 陳寬宏 (b. 1977) uses a small carving knife to shape subtle details of the statue’s long robes that hang over its lotus seat. Photograph taken by the author on June 11, 2018.

This study examines the birth of a single cult statue in the city of Taipei, detailing how the statue comes into being, from initial divination, to the actual artistic process, to the rites of consecration, and finally to the ritual installation of the cult statue on a patron’s altar, a progression that unfolds over the course of about fifteen months. During this time, through an integration of artistic and ritual processes, the single cult statue at the heart of this case study comes to be understood as an instantiation of the ancient Daoist god Guangcheng Zi 廣成子, the Master of Vast Attainment (see fig. 2). The article asks how we should understand the relationship between these artistic and ritual processes and the resulting spirit image that is born out of them, specifically in a way that approximates the perspective of those people involved in the statue’s commission, creation, and consecration.

Figure 2: Chen Kuanhong. The Sovereign Master of Vast Attainment (Guangcheng huangshi 廣成皇師). 2018. Hand-carved and hand-painted statue. Taiwanese stout camphor wood; color pigment and gold; plastic beads; thread; nylon fibers. Height: 18'' (一尺六寸). Photograph taken by the author on July 13, 2018.

In response, the author argues that the statue of Master Guangcheng emerges and endures in the context of its religious lifeworld not as a discrete entity, not as first an object of craftsmanship and then an object of devotion, but rather as an “assemblage,” a coming together of the people who contribute to it, the materials those people use for their contributions, and the specific spirits and divine powers those people invoke. What brings together and binds those people, materials, and spirits are the ritual and artistic processes involved in the statue’s development, from its initial conception to its ultimate enshrinement. Through these processes, the people who contribute to the statue may leave material traces on its physical exterior, visible markers of its creation and consecration (see fig. 3). Concurrently, and more importantly for the statue’s gradual movement toward divine instantiation, those same people leave immaterial traces of their presence and processes, as well as immaterial divine presences, all of which remains latent and hidden, gathered and bound together on, in, and around the assemblage of the statue.

Figure 3: During the ritual of consecration, a Daoist priest writes an apotropaic talisman on the upper back of the statue. Photograph taken by the author on July 18, 2018.

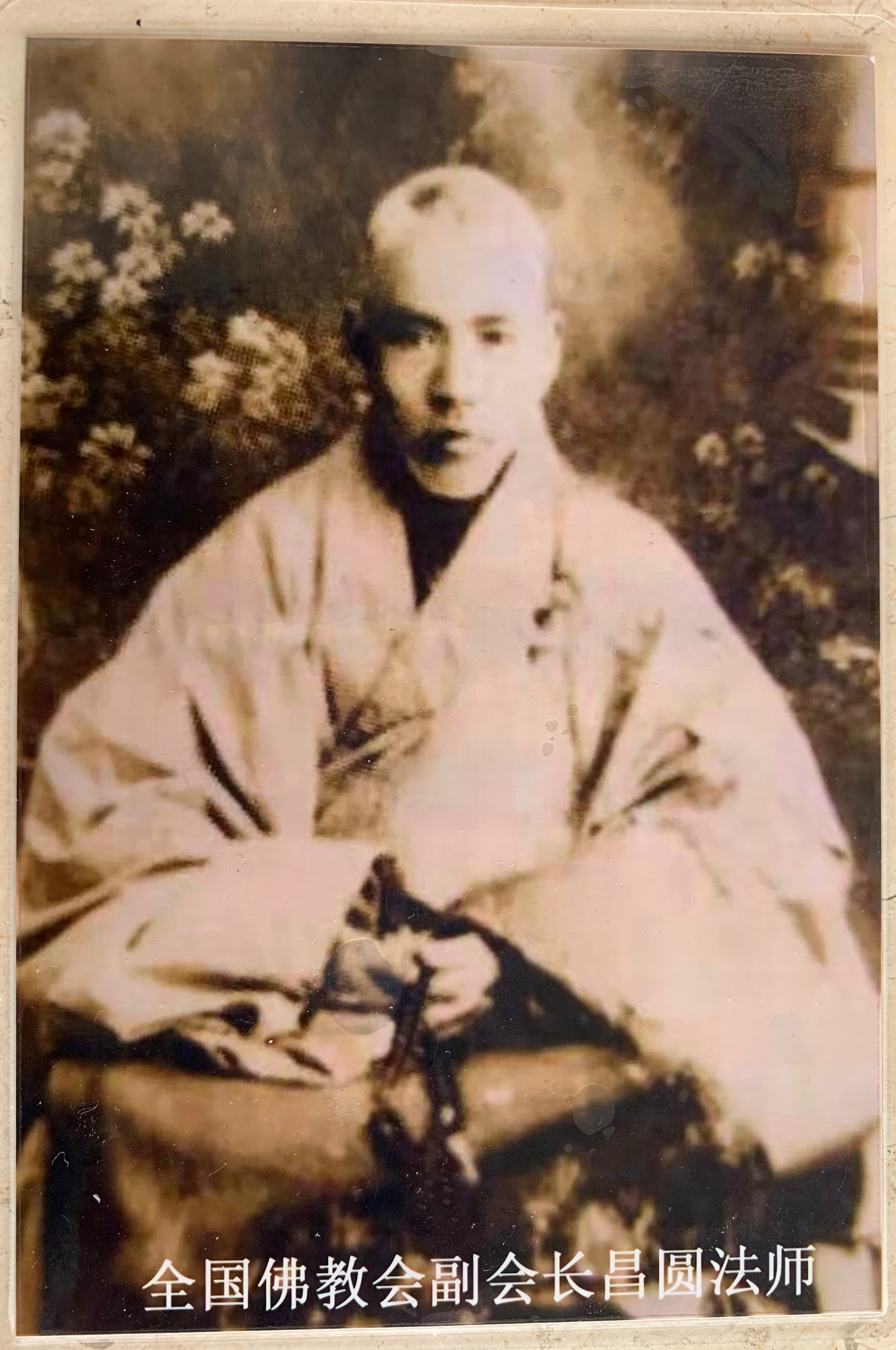

Monk Changyuan 昌圓 (1879–1945), Nuns in Chengdu, and Revaluation of Local Heritage: Voicing Local (In)Visible Narratives of Modern Sichuan Buddhism

Stefania Travagnin

In the peripheries of Chengdu, what was known as Pi xian 郫縣 in the Republican era, a stone with the sign ‘Śākyamuni Bridge’ (Shijia qiao 釋迦橋) names a one-century-old bridge. The bridge is so called to honor the local monk Changyuan 昌圓 (1879–1945) who was protagonist of its construction. Changyuan is also remembered in a few small Buddhist sites in the Pi xian area: the plaque of his lost pagoda is preserved at Zhongxing nunnery (Zhongxing si 中興寺), which also displays a short biography of the monk, well framed, in the main shrine hall. An inscription at Pingle monastery (Pingle si 平樂寺) reminds that Changyuan was pivotal in transforming the site into a Buddhist temple in the 1930s. And nuns from Zhuyin nunnery (Zhuyin si 竹隱寺) like to narrate the story of the young Wu Dechang 伍德昌, who spent a few years in close contact with the nuns, and inspired by them, especially by the abbess Fangchong 方崇 (1841–192?), decided to start his monastic career and so became the monk Changyuan. Photos of Changyuan are also found in Aidao nunnery (Aidao tang 愛道堂) too, in the center of Chengdu, as it was Changyuan who turned it into a nuns’ site. And he is also remembered at the nearby Jinsha nunnery (Jinsha an 金沙庵), where, in cooperation with the nun Nengjing 能靜 (1909–1993), he opened a school for nuns in the 1940s.

Figure 1: Portrait of the monk Changyuan (photo courtesy of Du Zhangming)

Figure 2: Śākyamuni Bridge (photo by Stefania Travagnin, 2019)

Spaces speak of their religious heritage in many ways, but too often only selected sites and figures are made visible protagonist of their histories. Buddhist figures like Changyuan, Fangchong, and Nengjing have been so far understudied, yet they were leaders in their communities, and authoritative voices of local Buddhism. My research seeks to redirect scholarly focus and give voice to monastics and institutions that have been so far invisible, bring the peripheries to the center of the study of Chinese religions, and revive a lost heritage. And so the invisible may eventually become (in)visible.

This article explores small institutions and marginal communities in Republican Chengdu, especially in the suburban regions Pi xian 郫縣 and Wenjiang xian 溫江縣, and it discusses connections between Changyuan and nuns through the analysis of local education projects.

Figure 3: Jinsha Nunnery 金沙庵, which hosted the Lotus Institute for Nuns (Lianzong nizhong yuan 蓮宗尼眾院) in the 1940s (photo by Stefania Travagnin, 2019)