Practicing Salvation: Meat-eating, Martyrdom, and Sacrifice as Religious Ideals in the Zhenkongjiao

Esmond Chuah Meng Soh

Figure 1: Devotees reciting the “Four Books in Five Volumes 四部五册” in front of an altar to the Zhenkongjiao in Singapore. Note the stylised character for “Emptiness 空” and “Center/Within 中” in a place-of-prominence, as well as the characters inscribed within them. “Five Refuges and Four Examinations 五皈四考.” Photograph by the author, December 15, 2019.

The Zhenkongjiao 真空教, alias the Great Way Within Emptiness 空中大道, is a Chinese sectarian religion that was founded in Jiangxi in late-Qing China, circa. 1862. Throughout late-Qing (1644-1911 CE) and Republican China (1911-1949 CE), the movement had a powerful presence in south-south-eastern China, where it expanded outside of its place-of-origin in southern Jiangxi to encapsulate the regions of Fujian and Guangdong. By the first few decades of the twentieth-century, the Zhenkongjiao’s leadership had also established various temples among Chinese communities in Southeast Asia, spanning from Malaya (and Singapore), as well as in Thailand and Indonesia. The rapid rise of the Zhenkongjiao during the turn of the century is related partially to the movement’s treatment of opium-addicts, which finds many similarities with the prohibitionist ideals endorsed by the Zailijiao 在理教 in northern China.

Although much research has been performed on this subject, the Zhenkongjiao’s opium-treatment efforts was only among many other unique aspects of religious practice in late-Qing and Republican China. In my article “Practicing Salvation: Meat-eating, Martyrdom, and Sacrifice as Religious Ideals in the Zhenkongjiao,” I shed light on two under-studied aspects of the Zhenkongjiao’s belief systems, namely its acceptance – and promotion – of meat-eating and meat-offerings, as well as its soteriology of sacrifice. By drawing upon hagiographies published and disseminated under the movement’s auspices from the 1920s onwards, I examine how the Zhenkongjiao framed its novel belief system within intermeshing (and competing) religious and philosophical outlooks contemporaneous with their time.

Figure 2: Food offerings from the “Five Mountains and the Five Seas" 五山五海 presented before a Zhenkongjiao altar, Singapore. Note the alternating arrangement of one dish of seafood (for example, cuttlefish balls) with meat (such as chicken or pork) to correspond with the ceremony’s name. Photograph by the author, December 15, 2019.

Readers who are familiar with the sectarian religion known as Luo Teachings 罗教 in late-imperial and Republican China (alias the Non-Action Teachings in the north无为教, and the Great Vehicle Teachings in the south 大乘教), for example, will notice that the movement’s adherents and its splinters – including the Great Way of Former Heaven 先天大道 and the Unity Movement 一贯道 – promoted life-long vegetarianism as a form of religious practice. The Zhenkongjiao’s hagiographies tell us that its founder, Liao Dipin 廖帝聘 (1827-1893), was first initiated into religious life under the tutelage of one such master under the Great Vehicle Teachings in Jiangxi.

However, throughout the lives of Liao and his disciples, they did not accept the precept of vegetarianism, on the grounds that the activity not only crowded out more important aspects of religious practice, such as the “Five Refuges and Four Examinations 五皈四考.” Various episodes in these hagiographies, for example, suggest that vegetarianism was a petty facade of spiritual practice that did not necessarily commensurate with the moral worth of its practitioners, some of whom were presented as hypocritical and practitioners of sorcery in these accounts. Likewise, through these hagiographies, we also get a glimpse into the social isolation that practitioners of vegetarian diets have to undergo, again testifying to the long and contested history of the practice in China.

Subsequent sections of my study related to Liao Dipin’s life – which has been juxtaposed alongside other crucial figures of Chinese and religious history by various hagiographers, including Confucius (551-479 BCE), the Song loyalist Yue Fei (1122-1142), and Jesus (circa. 4 BCE – 30 or 33 CE) – examine how hagiographers consistently situated the Zhenkongjiao’s leadership within a series of trial-like events, where they were expected to undertake unfair treatment in their pursuit of spiritual enlightenment. Explanatory notes attached to the “Five Refuges and the Four Examinations” made consistent reference to the need for initiates to undertake suffering, and Liao Dipin himself, according to all the hagiographies that I have consulted, agree that he was martyred after corrupt elites in Jiangxi tried to extort a bribe from him, testifying to the significance of this worldview in the Zhenkongjiao’s belief system.

This dimension of sacrifice is not limited to the hagiographical treatments of the lives of the Zhenkongjiao’s founder and patriarchs. It also informed the soteriology and rituals unique to the movement. Unlike many other Chinese religious traditions, who believe that the lives of animals need to be saved to benefit one’s spiritual practice, the Zhenkongjiao’s leadership advocated the ritualistic slaughter of animals in rituals that euphemistically known as “releasing flowers 放花,” alias “slaughtering livestock to worship the Way 宰性敬道.” According to the Zhenkongjiao’s cosmology, animal souls were capable of bearing the metaphysical ailments, sins, and burdens of human beings. Once they were released from their miserable experience of being an animal after ritual slaughter, it was believed that these animal souls would not only be able to benefit from a better afterlife but could also help their this-worldly sponsors escape disaster – literal and metaphorical alike – as well.

However, the Zhenkongjiao’s novel soteriology did not go unchallenged. Hagiographies tell of many wars of words between Buddhists and the Zhenkongjiao’s leadership, which likely reflected contemporary realities, where the movement had to fend-off challenges to its practices. For example, animal protection efforts in Republican China, as researchers have pointed out, grew with the help of Buddhist supporters, particularly when such discourses were couched within Social Darwinian perspectives in international politics. Yet, the Zhenkongjiao actively drew inspiration from aspects of Buddhist terms and cosmology to structure its own belief system, as well as broader images of meat-eating as national strength in Republican China, alongside traditional Chinese beliefs that the war-dead can be fed and placated with sanguinary offerings.

Finally, even though animal souls and bodies were believed to be able to take on their human sponsors sins and burdens, I argue that this belief extended to the Zhenkongjiao’s leadership. In these hagiographies, these masters literally take on the this-worldly pains and illnesses of their devotees, who believe that these ailments have been transferred from their own bodies and souls onto the self-sacrificing physique of these masters in rituals known as “Crossing the Way 过道.” Granted, much of the Zhenkongjiao’s beliefs remains unknown, and I hope that my research can shed much needed light on the intellectual history of a religious movement whose beliefs, soteriology and cosmology have been yet to be fully understood.

Ritual Techniques for Creating a Divine Persona in Late Imperial China: The Case of Daoist Law Enforcer Lord Wang

Vincent Goossaert

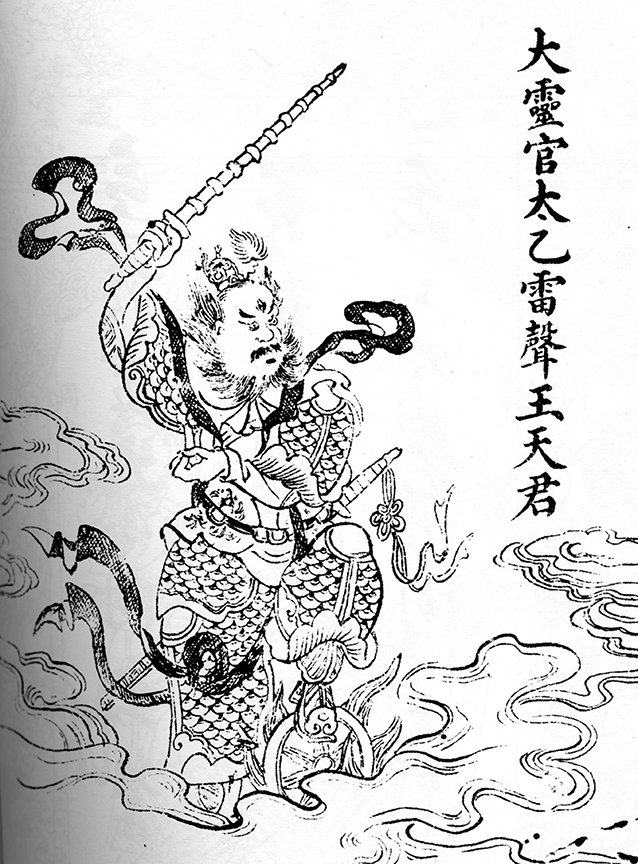

Figure 1: Lord Wang in the Guandi ming sheng zhenjing 關帝明聖眞經, Republican-period Hongda press (Shanghai) edition. This image is representative of Lord Wang’s depiction in many contexts, including such as here in spirit-written texts, where he usually appears at the beginning or the end of the volume. He has the martial vestments and attitude typical of Thunder gods, and wields his Iron whip, with which he pummels the sinners and vow-breakers.

Lord Wang (Wang lingguan 王靈官, Wang tianjun 王天君) is an ubiquitous god in late imperial and modern Chinese society, worshipped in different contexts, including temple processions, exorcistic rituals, popular pilgrimages, monastic ordinations, and elite spirit-writing cults. This article argues that his divine persona remains coherent in these different contexts, and that a reason for this coherence is that he is made present to its many audiences through ritual techniques (controlled spirit-possession, ritual theater, spirit-writing) that are consistent. As a result, his divine persona as the fearful enforcer of the divine code and guarantor of oaths and vows appears stable, from elite to popular contexts. The regular presence of Lord Wang in many spirit-writing groups (as instructor in ritual techniques and supervisor of the group members) further shows that these groups were not a separate realm of Chinese religion but an important actor in constant interaction with local cults and popular culture.

Towards a Buddhist History of Mount Tai

Claudia Wenzel

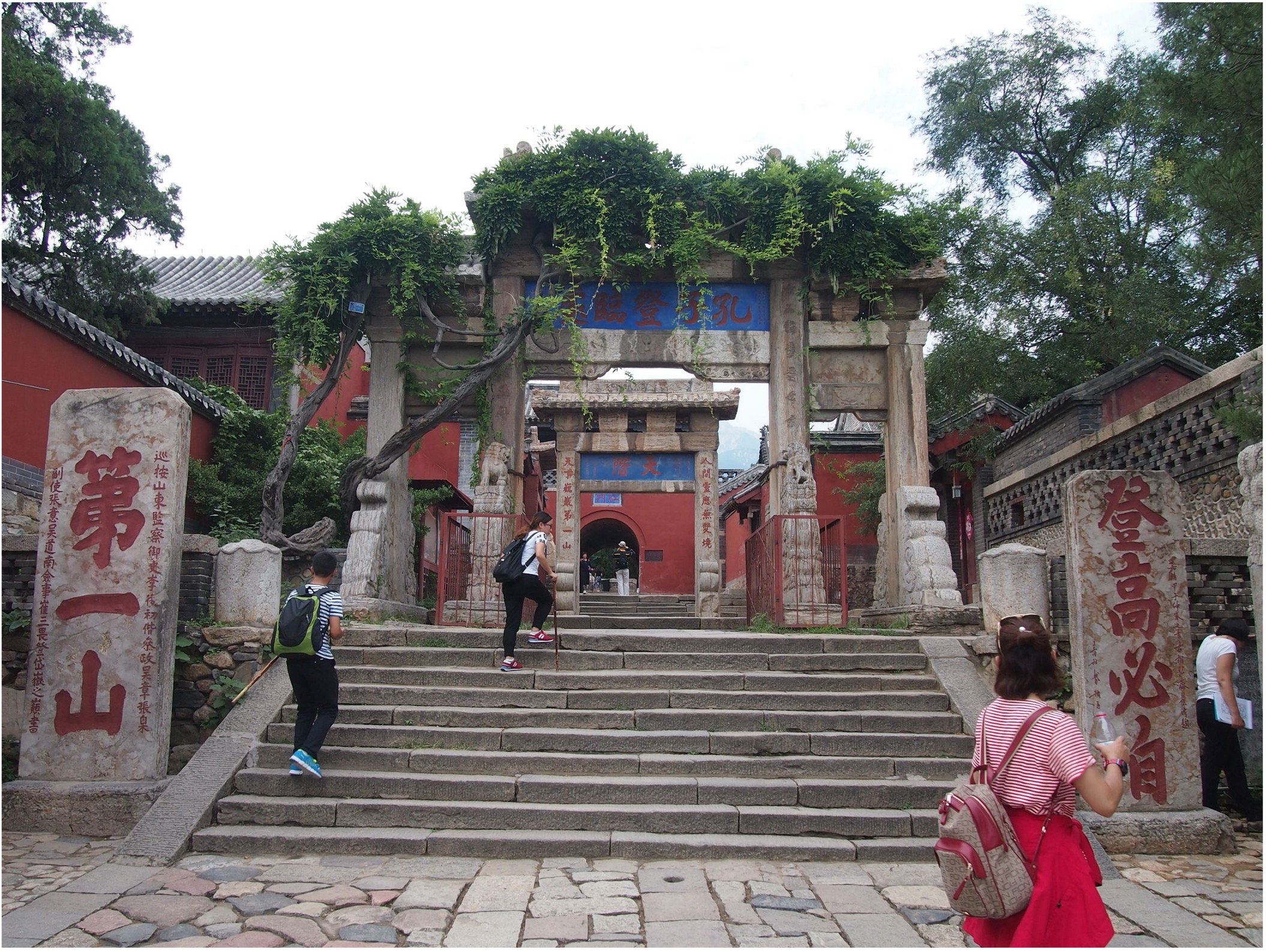

Mount Tai, the Sacred Peak of the East (dongyue 東嶽), has always played a crucial role in China’s cultural history. To this day, it attracts thousands of visitors and pilgrims, not only from China proper, but from the entire world. Its designation as “foremost mountain” (diyi shan 第一山) refers to the highest mountain in the land of Lu 鲁, once climbed by Confucius, but also to the high standing this mountain range has always enjoyed as a national symbol for China.

Figure 1: Mount Tai’s pilgrim path near the Red Gate (Hongmen 紅門).

In cultural memory, the mountain is perceived mainly as a site where the indigenous Daoist religion has been practiced for many centuries, and where Chinese emperors performed rites essential for the state cult by making offerings to Heaven. The Buddhist history of Mount Tai has so far largely been neglected, what is all the more surprising, because the most ancient among the surviving stone inscriptions of Mount Tai is the giant Diamond Sutra of Sutra Stone Valley, an impressive early Buddhist artefact created during the Northern Qi dynasty (550-577).

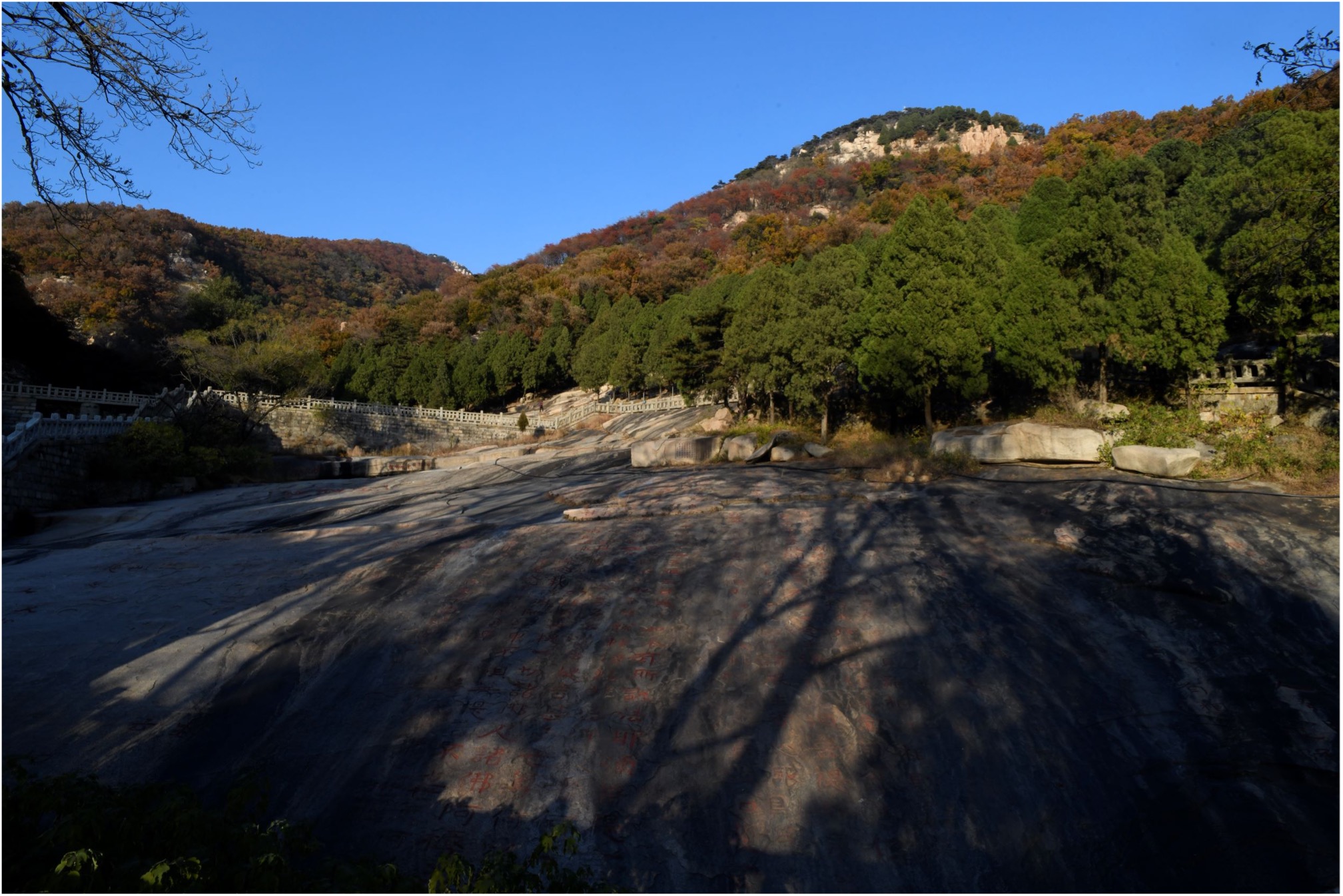

Figure 2: A view of Sutra Stone Valley 經石峪 where the giant Diamond Sutra inscription is carved.

The Diamond Sutra inscription, located at a scenic spot on the prominent yang side of Mount Tai, i.e., the side south of the main summit, evidences the succesful Buddhist acculturation of Mount Tai in the second half of the sixth century. As a cultural monument, the inscription has long been cherished for its outstanding calligraphy and the beauty of its surrounding scenery, but its origins are in the dark. During my second visit to Mount Tai, I thought that it would be worthwhile to make some further investigations into the Buddhist history of the Mount Tai region, including those Buddhist establishments found at the yin side of the mountain, i.e., to the north of the main summit.

Here, we find the ruins of two large monasteries that have shaped the Buddhist history of the Shandong region for centuries, Lingyan Monastery 靈巖寺, and the famous Shentong Monastery 神通寺, which is located in Licheng 歷城 in the municipality of Ji’nan 濟南市. Both monasteries have laid claim on the semi-legendary monk Senglang 僧朗 (ca. 315–400) who is said to have established the first Buddhist monastery on Mount Tai, and who is generally honored as the person who missionized all of Shandong Province from the rear side of Mount Tai, so to say. In my paper, I will show that this not necessarily so, as there is also early archaeological evidence for Buddhist activities all around the sacred mountain.

Figure 3: The famous four-gate stupa of Shentong Monastery, one of the earliest surviving Buddhist stone buildings in China.

My investigations into the traditional founding legend about monk Senglang also took me to places less visited by tourists. Particularly charming is the present Jade Spring Temple (Yuquan Si 玉泉寺),located only six kilometers north of Mount Tai’s main summit. This place claims an equally long history reaching back into the past. Steles still extant on-site record the ancient name Gushan Monastery 谷山寺 for this place and transmit a founding legend around the monk Sengyi 僧意 (dates unknown) who is said to have somehow been involved in the missionary activities of Senglang. Buddhism is still practiced in Jade Spring Temple, where visitors bow their heads at the feet of the large Buddha statue inside the modern main hall. In addition, a path encircles the temple grounds, along which more mysterious traces of old can be discovered, including the “eastern and western footprints of the Buddha” and some strange rock formations in auspicious shapes. On a cliff inside the entrance courtyard, an image of the “Buddha’s shadow” 佛影 was carved at an unknown date. The ancient Gushan Monastery may have added these ancient traces of an explicitly Buddhist pedigree to the numerous historical sites with sublime traces that are so prominent on Mount Tai. While it is very difficult to come to any reliable estimation about the age of these Buddhist traces, the giant ginkgo trees in front of the flight of steps leading to the main hall may easily be one thousand years old, and may well have already stood there when Jade Spring Temple was founded as Gushan Monastery at some point in time before the seventh century.

Figure 4: One of two giant ginkgo trees in front of the flight of steps that leads up to the main hall of Jade Spring Temple, the ancient Gushan Monastery.

My upcoming paper includes these findings about Buddhist sites in the larger region of Mount Tai. By surveying material and textual evidence from the late fifth century onwards, I have attempted to trace the Buddhist acculturation of this Sacred Peak of the East. Whatever archaeological evidence was available was read alongside the traditional founding legend about monk Senglang, the alleged founder of the “first monastery” on the mountain. I hope that my paper can help to tie the most impressive early Buddhist artefact—the giant Diamond Sutra inscribed in Sutra Stone Valley during the Northern Qi dynasty—into the network of sites that I visited on Mount Tai.